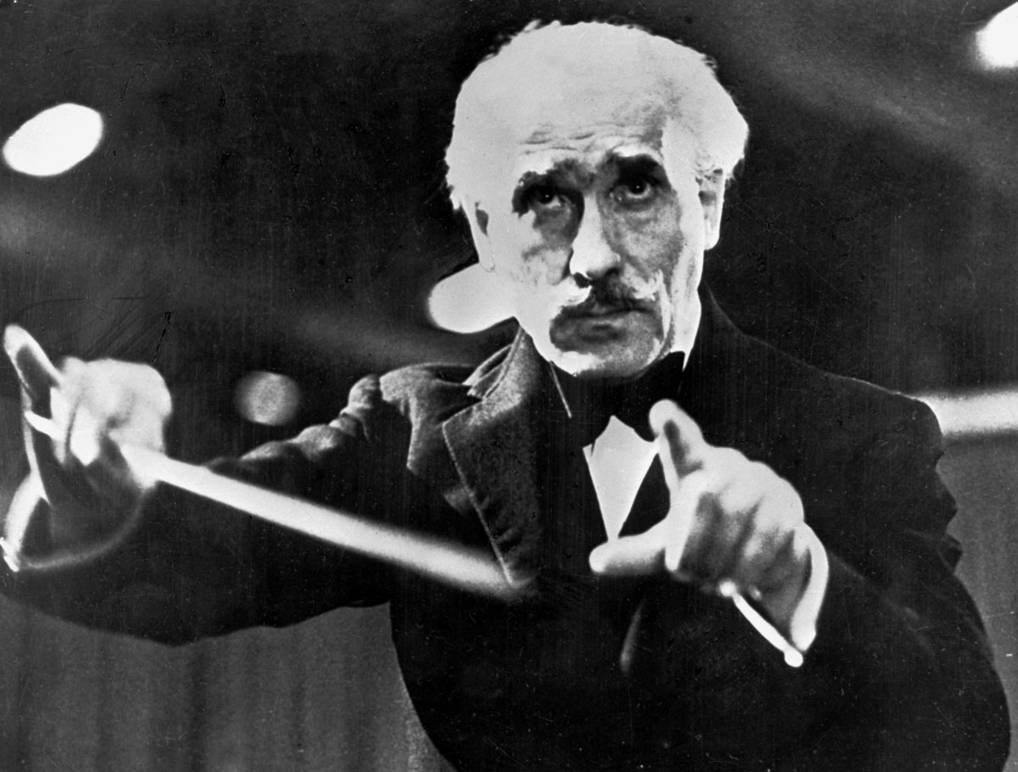

A New Biography—“Toscanini: Musician of Conscience”

What do Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), and Lorin Maazel (1930-2014) have in common? They’re all among the greatest conductors of all time. But who’s the best? Though one can’t say for sure, most music-lovers will point to Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957).

The Italian first established himself as a talented conductor at the age of 19. Over the next few decades he worked with the most prestigious opera houses and symphonies across the globe, including La Scala, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and the NBC Symphony Orchestra. At 89 years old, Toscanini died in New York on January 16, 1957.

To mark the 150th anniversary of his birth, eminent music historian, Harvey Sachs, published Toscanini-Musician of Conscience this past month with Liveright Publishing.

Sachs, who has nine other books under his belt and writes for The New York Times, already published a biography of the great virtuoso in 1978, but this isn’t simply a new edition. Thanks to the new availability of huge archives of documents and letters—in 2002 he edited The Letters of Arturo Toscanini—this is an entirely new study at 944 pages, twice as long as the first biography.

Sachs draws on this enormous range of evidence in meticulous detail. The result is a sweeping exploration of Toscanini’s personal and professional life from musical to political, beginning with his birth in Parma to his final days in NYC. And despite the book’s heft, it’s undoubtedly stimulating. In fact, Toscanini’s boisterous humanity truly does come alive.

The biography presents him as who he was: generous, courageous, and principled, but with his flaws in tact, particularly his explosive temper and countless extramarital affairs. Yes, to the reader’s delight, Sachs does treat with a bit of gossip, but it’s all integral to the tale at hand.

Of course, Sachs revealed how Toscanini’s first job came by accident. As the story goes, in 1886, he was on tour in Rio de Janeiro engaged as a cellist, but the audience refused to listen to the scheduled maestro. After a subscriber ran in shouting, “Isn’t there anyone in the orchestra who can conduct Aida?'” the teenager, who did know the entire work from memory, agreed to take charge.

In fact, he had a phenomenal photographic memory and never used printed scores while performing. By the end of his career he had memorized 250 symphonic works and more than 100 operas.

Though he was leading ensembles all over the world to rave reviews, this came at a cost. In pursuit of perfection, he barely slept five hours a night or saw his children very often.

Beyond the podium, Toscanini was a fearless spokesman for democracy and freedom. He often risked his life to speak out against the evils of fascism, even refusing to conduct the “patriotic music” demanded by Mussolini’s lawless supporters.

Definitive, absorbing, monumental, and captivating, the biography also allows the reader to encounter other fascinating figures with whom Toscanini interacted, like Puccini, Verdi, Mahler, Horowitz, and the relatives of Richard Wagner.

And though those drawn to music, culture, and politics will all revel in the book’s glory, a layman can easily enjoy it, too, thanks to Sachs’s helpful reminders of important characters and explanations of basic concepts—not to mention his fluent and gripping writing style.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.