Michelangelo Divine Draftsman and Designer - How a Monument Comes Alive

When we talk about Italy, whether as a child in an elementary school or a as a tourist, there are always these three words: Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museums. Even those of a certain age like me remember with particular anguish, which later on became absolute joy, the modern restoration that began in 1979 of the lunettes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling and that continued until the restoration of the entire work. On December 11, 1989, the process was documented by the Japanese photographer Takashi Okamura as it brought back the ancient splendor and colors a work that had lost its original power.

Do you remember all the controversies at the time? And the people who identified Michelangelo with a faded painting rather than a vivid incarnation? We can definitely say that Michelangelo has always made people talking a lot about himself.

Painter, sculptor, architect, and poet, Michelangelo, one of the most famous artists of the Italian Renaissance, was born in Tuscany on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, a little village close to Arezzo. Michelangelo’s father, Lodovico, was serving as a magistrate there when he recorded the birth of his second of five sons to his wife, Francesca Neri. As critic Holland Cotter correctly noted in his article in the New York Times, the exhibit “Michelangelo Divine Draftsman and Designer” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a monument to a monument. As Cotter said, ‘’It is a one-stop event with a nonextendable three-month run, which is the maximum exposure to light, even at dusk-level, that the drawings can safely stand‘’.

To explore more fully the idea of the exhibition, we asked questions of Carmen C. Bambach, a good friend of mine, curator of the exhibition, as well as curator at the Museum's Department of Drawing and Prints. We wanted to know more about the work, the commitment and the torment behind this and every other major exhibition.

Is the exhibition about Michelangelo a sign of devotion to an artist you've always loved? Is it your life’s commitment?

“Michelangelo Divine Draftsman and Designer is the result of a life-long commitment to study this great artist and is in many ways a professional dream come true. I was born and raised in Chile until I was a young teenager, when my family emigrated to the United States, where my inclination during my early life was to become an artist. At that young age, I was very focused on drawing copies after photographs of Michelangelo’s frescoes and sculptures to train my eye and hand. Michelangelo was my love throughout my college years and graduate studies in art history at Yale University, but the concentrated efforts, research, and serious planning for the exhibition at the Met have occurred during the last eight years. Our focus in the show is primarily on the originality of the artist. At a time when much of our visual experience -- as students, scholars, or the general public -- is inundated by digital images, it is a rare privilege to see so many original works by Michelangelo gathered together in an event designed for close looking, contemplation, and even reverie. The Met’s exhibition explores the concept of Michelangelo the Divin’ disegnatore, the divine draftsman and designer, with a selection of more than 200 extremely rare works, selected from almost 50 museums and private collections in Europe and the United States."

What did you find out about Michelangelo that you did not know before? Do you see him in a different way now?

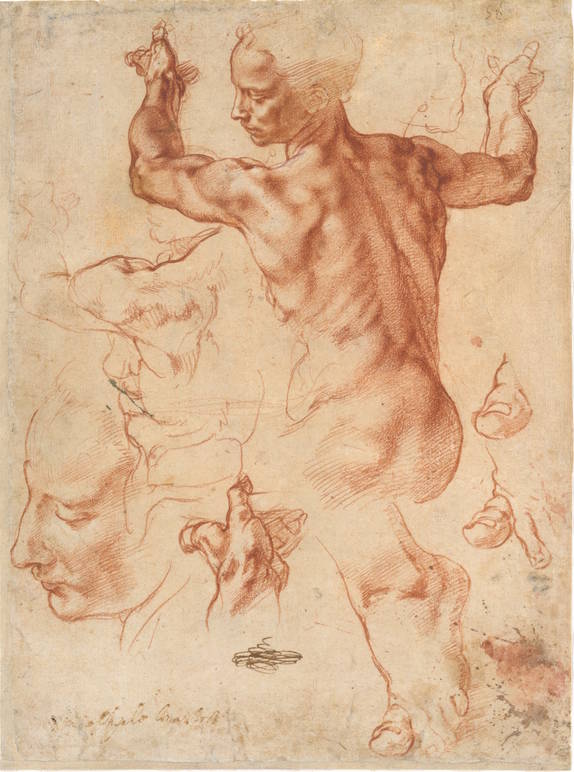

"In preparing the Met’s exhibition and making the selection of the over 200 works, it became especially important to focus the attention on Michelangelo’s disegno, its meanings and implications in the widest possible sense. Michelangelo’s energy and imagination – his “fantasia” -- were uncontainable up until his death at 88 years of age, and the exhibition attempts to illustrate his enormous versatility as an artist in the selection of works. The exhibition showcases the 133 drawings by Michelangelo, which is a very large representation of his work. There are also three of his sculptures and a wood architectural model from the Fabbrica di San Pietro in order to illustrate the continuities in his artistic process and the monumentality of scale in his conception of the human figure and architecture. The exhibition also includes drawings, paintings, and sculptures by other artists that represent Michelangelo in the art world of his time."

The audience visiting Michelangelo is sometimes a distracted audience. What should those people absolutely not miss about this exhibition?

"The design of the exhibition includes many monumental works which create vistas as points of attraction for the public, as enticements to keep going from one room of the exhibition to another. The vistas are of Michelangelo’s marble sculptures and of his largest compositions all seen in dramatic lighting. Of course, the visitor should not miss the room at the midpoint in the exhibition that contains an enormous reproduction of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, the scaffolding, and Michelangelo’s original studies for the Sistine. The reproduction of the Sistine Ceiling can be seen floating above almost at the entrance of the exhibition so that the visitor begins the show with that as a destination."

Back to the Sistine restoration, I want to underline that the preliminary experimentation began in 1979. The restoration team included Gianluigi Colalucci, Maurizio Rossi, Piergiorgio Bonetti, and Bruno Baratti, who took as guidelines the rules for the restoration of works of art established in 1978 by Carlo Pietrangeli, director of the Vatican Laboratory for the Restoration of Paintings. The first stage of the work took place between June 1980 and October 1984 and the vault was completed in 1989. The final stage was the restoration of the wall frescoes, approved in 1994 and open to the public on December 11, 1999.

Holland Cotter also wrote that “this exhibition has made you revisit the original Renaissance concept of design, disegno, as a theoretical category, an aesthetic and ethical end in itself?” True?

"Yes, in commenting in detail about Michelangelo’s 'disegno' Holland got to the very pulse of the Met’s exhibition in his thoughtful review. Michelangelo’s conception of “disegno” (in the sense of design and drawing) provided the very foundation of his art, and he understood it in a profoundly metaphysical sense. In Michelangelo’s creative process the work of the mind, the eye, and the hand of the artist are interconnected in a continuum in which the intellectual and the manual production of art exist as one, and are inseparable dimensions of creativity. Disegno unified Michelangelo’s activity as sculptor, painter, and architect. It was very important to demonstrate to the viewer this ineffable, continuous connection of mind, eye, and hand in the sequences of drawings we presented. Many of the sequences of drawings reveal that for Michelangelo drawing was a very rich and functional language of expression, as well as an act of love. His gift drawings to his friends are the jewels of Michelangelo’s disegno, and those given to for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, for instance, are all reunited in the exhibition. Michelangelo’s art also emphasizes the monumental, the permanent (even wishfully, the eternal), and the very execution of the work “by his hand” -- “di sua mano,” as so many documents and letters by his contemporaries confirm. The authenticity of Michelangelo’s hand in drawing and design is a leading theme in the exhibition."

Michelangelo’s lover Tommaso dei Cavalieri(1509–1587), was an exceptionally handsome nobleman whose appearance seemed to have fit the artist's notions of ideal masculine beauty. Cavalieri was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57 and he was the object of the greatest expression of Michelangelo's love. He dedicated approximately 30 of his total 300 poems to Cavalieri, which made them the artist's largest sequence of poems. The homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grandnephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. John Addington Symonds, the British poet, critic, and gay activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and by writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893. Michelangelo also had a strong relationship with Vittoria Colonna, who influenced Michelangelo's life the most. He met her in Rome, where he spent the last 30 years of his life. Their friendship came late, when he was 61, lasted until Colonna’s death in 1547. It seems to have seriously changed by encouraging his move in a contemplative direction and bringing a new, soft grace to his work.

What does Michelangelo’s art teach a contemporary artist?

"Michelangelo’s philosophy of disegno seems to me to provide very important avenues for new ways of thinking about our contemporary art world. The example of Michelangelo can help us refocus our attention on the work by the artist’s hand, di sua mano, which can and should be seen as intrinsic to the creation of art. In our contemporary art world, it seems to me a very productive exercise to rethink how we approach the relationships of the conceptual and the technical execution of art. Today, artists, collectors, and the art public have often felt a certain anxiety about admiring or even valuing the technical virtuosity of a work of art. Instead, the importance and value go mostly into conceptual aspects and ideas behind the work. Many contemporary artists have especially diminished the value of the execution of a work of art so that a basic sketch can be given to studio assistants from which to paint or to create a series of images. A sculptor in Carrara, for example, can create an entire monumental sculpture in marble based on a small conceptual sketch by an artist. Similarly, we have often tended to emphasize the ephemeral in art and give little thought to the permanent."

In this field I remember that Jackson Pollock, one of the leading painters of the twentieth century, one who undermined the rules of western figurative art and dissolving the last bastions of Renaissance perspective was influenced by Michelangelo. The young Pollock, still undecided whether he wanted to become a painter or a sculptor, studied and reflected upon Michelangelo’s work: there are drawings by Pollock that reproduce the ‘naked’ in the Sistine Chapel, the Cumaean Sibyl, and The Prophet Jonah, certain figures in the Flood, Adam in his famous position, and studies of positions and drapery in the Judgement. A small exhibition of Michelangelo’s influence was held in Florence in 2014.

An ambitious project with a prestigious institution can create some competition in the art world. What was the reaction of international lenders and, in particular, of Italian colleagues?

"The Met’s show has been eight years in the making, including the research and the many loan negotiations. From the very beginning, our colleagues in the museums of Europe and the United States rallied to support this project with loans, and once we had secured a core group of works, more institutions began to collaborate . Both European and American museums and private collectors have been beyond extraordinary in their generosity with loans, and they often performed miracles to get these loans approved in time for the Met’s exhibition. Very importantly, Italy has lent a total of 57 works,, most of them by Michelangelo’s hand. This large group of impressive loans has made a magnificent contribution to the show. Of the nearly 50 lenders of works of art to the Met's show, I would like to single out especially the Royal Collection of Windsor Castle (Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II); the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford; the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence; the Casa Buonarroti in Florence; the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples; the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London."

---

Carmen C. Bambach, Curator of Italian and Spanish drawings (BA, MA, and PhD, Yale University; fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences), is a specialist in Italian Renaissance art. She is the author of Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300–1600 (Cambridge University Press, 1999) and Una eredità difficile: i disegni ed i manoscritti di Leonardo tra mito e documento (Florence, 2009), more than 70 scholarly articles, and 10 exhibition catalogues, including Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer (2017), The Drawings of Bronzino (2010), An Italian Journey(2010), Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman (2003), Correggio and Parmigianino (2000), and The Drawings of Filippino Lippi and His Circle (1997)

---

Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until 12 February 2018)

Accompanied by a catalogue by the organizing curator of the exhibition, Carmen C. Bambach—an authoritative volume that examines the Renaissance master as "the divine draftsman and designer" whose work, according to Giorgio Vasari, embodied the unity of the arts.

Many thanks to Carmen Banbach, Mauro Mussulin and the The Metropolitan Museum

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.