Il Segreto di Majorana: a Graphic Novel on the Elusive Life of the Sicilian Scientist

These are some of the unanswered questions in the mysterious life of Ettore Majorana, one of the most important physicists in history, a man from Catania who along with other talented individuals such as Enrico Fermi, revolutionized the field of Science forever. His discoveries, theories and studies, along with his life are undeniably fascinating and it makes sense that they would inspire narrative adaptations.

“Il Segreto di Majorana” is a very unique and creative book, a graphic novel, penned by

Francesca Riccioni with Silvia Rocchi, the illustrator, that takes on the complex task of capturing this man. Thanks to her scientific background in Physics and her love for the arts, Francesca Riccioni has managed to bring those passions together in her work.

This book also becomes an opportunity to show the brilliance of the young creative and scientific minds of Italy, as well as learn about some of his prominent figures of the past such as Ettore Majorana. I interviewed Francesca on her wonderful new graphic novel which has been published in Italy by Rizzoli and will hopefully cross the ocean soon.

Some people still look down at graphic novels as something specifically for kids or teenagers, or as a genre focused on fantasy or exaggerated characters and themes, but more and more often it has become the vehicle for basically any powerful adult story, artist or idea.

From “the Fith Beatlle” , a Brian Epstein biography that panders to the baby-boomers, to the famous “Persepolis” which details the turmoil and coming of age of a young gifted girl in Iran and so on: there is something for every taste and with literary complexity both in form and content.

“Il Segreto di Majorana” examines this physicist through a narrative and creative eye and it’s not looking to dumbing things down.

A central theme in the book (Il segreto di Majorana) is Elusiveness. The elusiveness of a man, Majorana, who avoided definitions, who mysteriously disappeared and who literally tried to find the "elusive side" of matter: anti-matter. He also lived a bit of an elusive life, abstract, never fully satisfied and grounded. Do you agree? When did you encounter the figure of Majorana first in your life and when and how did you decide to focus on this aspect?

I completely agree. In my books, I often try to explore the human side of scientists linking that with their work later; this allows me to bring out and deliver scientific facts to the reader through a new channel: the empathy with the scientist’s life. I like to think that scientific creativity is every bit as powerful as artistic creativity.

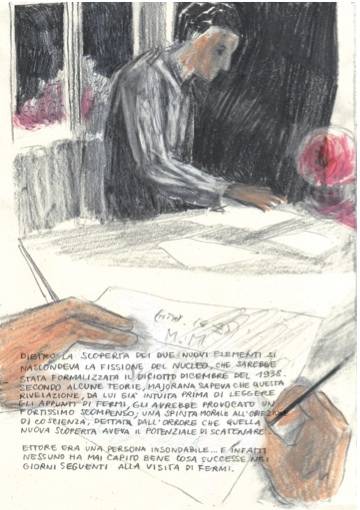

The metaphoric parallel between Ettore and his particle model, Majorana’s fermion, is so self-evident that I realized that was the perfect key to communicate his core concepts in a narrative story.

The particle shares the same defining traits with its “creator”; among all of them, the fact that it’s the one that has the least interactions out of all the particles of the standard model.

His elusiveness, his being unattainable, is a kind of existence that becomes paradoxical, that drives someone towards delusional worlds, towards exaggerated theoretical structures in one’s research, sometimes even a waste of one’s energy, towards the kind of life Majorana lived, the never-ending search for him after his disappearance and his all-consuming research on the particle that still affects all of the scientific community today.

With “Il Segreto di Majorana” I wanted to focus on a more intimate and personal dimension, and even Leo’s results and intuitions (*Leo is the modern protagonist of the graphic novel, a young researcher in California) in the fields of nano-technology mirror this intention, because it’s a field specialized in minuscule elements instead of, for example, something like the particles’ big accelerators.

I can’t recall the exact moment when I encountered Ettore Majorana and his life-story. It was probably during my childhood... I think. My mother is a mathematician and has always told us stories about scientists.

On a similar note, there is a quote in the book : “The concept of existence within absence, forgive this play on words, has defined the hidden life of Ettore Majorana after his disappearance, and that’s what has lead me to identify his particle, the most evanescent one”.

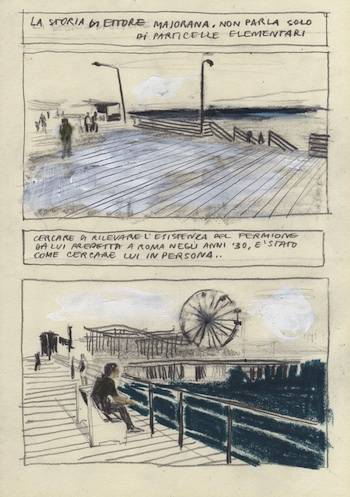

And I noticed that - compared to most graphic novels - the drawing style (watercolors, sketches and storyboard-type of scenes) reflects that “absence”, that unclear but sometimes almost dreamy quality you project on the character. The pictures seem restless, like they don’t want to stay still and tell you notions, simple facts.

How did this translate into the aesthetics of the book? Was that done on purpose?

I have always been intrigued by this concept, this process, very similar to how our memory works - but that then goes even beyond that - it’s a strange process that prompts us to re-play or re-situate in the present people or situations from the past, that brings them back to life, craving them, re-contextualizing them: I called it “presence within absence” and, to me, what comes the closest to describe it, is the Quantum state of a particle that is 50% there, but it’s also 50% not there.

And it does reflect what happened to Ettore Majorana, who disappeared in 1938, but who left a mark, with people (at least in Italy) still talking about him to this day, still searching for him after years everywhere; he undeniably still exists even if he’s not here with us. In a much more down to earth way, this process has become more tangible with modern social networks: people are not able to fully experience the actual absence of a person anymore, who then becomes a more symbolic and illusory presence.

We all take part, some more some less, in a collective culture to which “Il segreto di Majorana” responds to, in a way, with a veiled criticism, trying to invite the readers to respect such a difficult and personal choice of not wanting to speak, to say what hasn’t been said, of wanting to unchain oneself from a certain kind of unhealthy behavior.

That’s why an illustrator like Silvia Rocchi is, in my opinion, perfect to fully immerse us in this kind of atmosphere. Her style is tormented, emotional and yet dry. The “shots” are framed through a private and intimate point of view, honest and direct at the same time. Silvia also often uses experimental printing techniques in her books that help the narration. I found her idea of using calcographic engravings as an abstract way to interpret the invisible world of particles, very fascinating.

I really liked the idea (in the graphic novel) of going back and forth between the present and the past, in an original way, especially because the protagonists of the parts set in modern times, Leo and Amanda, are Italians abroad.

Young researchers, students, globe-trotters, people who have lives, jobs, brains and relationships “in-between”. Not necessarily split in two halves, or experiencing weaker links between them, but with more of a borderless and wireless approach to life. What was your thought process in creating this narrative framework? How does this connect with Majorana’s life or your life?

I actually never thought about it this way, but thank you for making me realize this connection. Technically the part of the book set in modern times has a precise narrative goal, since i decided I didn’t want to get into all the investigations following the disappearance of the theoretical physicist, because, as I mentioned before, I wanted to respect his wishes for “privacy” when he decided to run away. Leo and Amanda are also important to underline how every figure of the past, every 20th century’s idol, every historical idea, goes through an array of interpretations and that any reflection nowadays is merely a subjective impression, a thought, a personal projection or identification.

But when you think about it, yes the two protagonists, who are not completely in sync with their daily routine, while talking about Ettore, they experiment on each other and they both entertain the idea of an escape, or fiddle with its nuances.

There is something to be said about how, nowadays, people are used to travel, move constantly, and try to understand how they see their roots, or the various ways they actually plant them at some point, somewhere, without feeling trapped.

I think this goes hand in hand with how many more possibilities we have now, depending on one’s life and circumstances or country of origin, to build, to make new choices, to feel in control of our decisions.

Do you think Italian graphic novels are becoming more and more successful in Italy? Why now?

I’m not 100% sure I can give a conclusive answer on this. I do think though that, compared to a few years ago, there is a far more specific and structured response to this genre, in terms of publishing, more attention.

For example this year graphic novels had a pretty important role and were finally accepted as a legitimate genre at the Salone del Libro in Turin (Turin’s annual Book fair, a prestigious event in Italy) with a big section of the fair dedicated to them and many events and presentations. There is still a bit of a “niche” audience that usually likes comic books, but I think that the interest of the general public is growing, who is starting to fully enjoy an illustrated story with the same satisfaction, if not more, of a traditional novel. I hope this is a trend that continues!

This book is about Ettore Majorana, but you also published another graphic novel about a different scientist, Alan Turing, "ENIGMA. La strana vita di Alan Turing” in 2012.

Numerous aspects of Turing’s life have made it to the silver screen. The most successful is obviously ’The Imitation Game” (2014) with Benedict Cumberbatch, a movie that I liked because, much like your graphic novel, it brought central theoretical concepts to the surface through dramatic moments and crucial “winks” to the way we perceive technology today, in a deeper sense.

“Il Segreto di Majorana” feels somewhat like a movie script in terms of structure too. Do you ever get inspired by cinema? Could Majorana or any other scientist have a movie today that is less biopic and more structured around their ideas?

Thank you so much for this comparison but actually movies are not necessarily my first source of inspiration. I prefer to start from reality, my travels, those I met, the feelings I had, the photos I took, the kind of themes that are relevant to today’s world: ideas that I start to question, to criticize, or that I’m never too sure if they are ready to be shared with an audience, if they will interest other people, and maybe even enrich their point of view.

I don’t really love the kind of works of art that stem solely from an individual’s “ego” or stylize everything, or even sometimes I don’t adore pure entertainment, but I like the trigger, the invitation to think about something in new ways, to experiment with new feelings. The structure of “Il Segreto di Majorana” doesn’t simply follow the biopic genre, but, as you pointed out, the scientific ideas of the man in question, his research that has arrived to us intact and influences today’s discoveries.

Obviously a movie that could capture this “red thread” would seem more interesting to me and I would feel more involved because it would challenge the way I think, or make me think about today’s world.

You often combined your scientific background with your creative work. And I think it’s important to mention that while these are not educational books per se, one learns a great deal reading them. The lesson doesn’t come off as exposition, but you do get a bit of a didactic reenactment of themes, ideas, and even historical elements. Can you tell us about the moment that these two passions converged for you? Do you think that this approach would teach more about science to people?

This was always the case, as far as my life is concerned. In my family, my mother is a mathematician, my grandfather collected paintings of early 20th century Italian artists, my father loves fashion and design and I always received inputs from both the scientific and the artistic world.

Then I was lucky enough to work on my doctoral thesis (*Francesca has a degree in Physics obtained in Pisa) at an MRI lab where I could see extremely detailed images of the brain. Those NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) pictures are wonderful, in my opinion, and the techniques needed to capture them fascinated me: they are also full of data and useful information but that doesn’t make them any less intriguing.

That’s exactly how I would like my books to be,hard work! Albert Einstein used to say that creativity is nothing but intelligence having fun. I love contemporary art, electronic music, other creative fields that combine scientific/technological elements.

I also obtained a master in Science Communications at ISSAS (International superior school of advanced studies) in Trieste, Italy and I believe that everything we learn, not just through an educational ‘top-down’ approach, depends on the needs of who’s receiving that knowledge, but also on the intentions of those passing it on, communicating: when these two needs meet it’s when there is an interaction at the same level (peer-to-peer).

The intention behind the way I write is not necessarily to teach Science, but to make people more aware by opening some pre-existing files in their head, that while living our modern lives we also “live” Science on a daily basis.

What was special about this collaboration? Can you tell me more about Silvia Rocchi?

Working with Silvia was magical! I was already writing the book about Majorana, but I was still looking for an illustrator. During the BilBOlbul, a Comic Book Festival in Bologna, I attended the presentation of her first major graphic novel, "Ci sono notti che non accadono mai", a book inspired by the poetry of Alda Merini, an Italian poetess, and I fell in love with her drawings.

The theoretical connection between her style and the story I was working on was perfect. Without thinking twice about it, I asked her if she wanted to collaborate on a story that was about matter and anti-matter and she immediately said yes.

In Italy we are still far from the idea that a comic book artist can actually be considered an Artist, but I think she’s far more of a full artist than someone who simply draws comic books; she’s an artist who loves books so much to the point that she decided to become an author and let her drawings speak for her.

We were in agreement about everything we worked on, without any creative fight, and we always trusted each other’s instincts. We were transparent about sharing our different views, when needed, in order to come to a mutual solution. Silvia usually works by herself and her style is very personal, but I felt that the story fit her completely and none of us would have lost any kind of authenticity. I was curious about working with her. The book came out exactly the way we wanted. Quiet and intimate, restless and unique, just like Ettore!

When I reviewed and analyzed your previous graphic novel I mentioned that it brought "attention to the scientific side of Italy, a side that is often a bit overlooked.” Just recently there was an exhibit in NYC about Italian technological excellence iacelanguage. It’s incredible to think how many things we use today that weren’t actually invented or developed, for example, in Northern California in the Silicon Valley... but in Piedmont, Italy thanks to, among many, Olivetti; or how complex technologies, designs and systems we use today come from various over-looked Italians of the past or geniuses. What are ways to emphasize the scientific side of Italy to let its most brilliant mind emerge? Are you proud that your graphic novel could do that?

This is a pretty hard question. There are lots of ways to promote scientific culture abroad and the so called “Italian genius”. Even a graphic novel can do that of course, and I am definitely proud of that. In my opinion I don’t think that talent is necessarily connected to a geographic location, not just in the scientific world.

I’m not a sociologist but I think, if anything, one could look at the social and political forces at play: how does one place value certain resources and recognize the talents that were born and grew within one’s national borders? And once they are out in the open, how does a state help in providing and protecting said talent and promote them in the world? I can only answer this question with more questions, so sorry!!

What would you ask Majorana if you could meet him today? Or what would you talk about? Would it be in Sicily or on the coasts of California (where part of the book is set), or nowhere in particular?

Wow, I think I’d probably spend at least 10 minutes in pure awe, starstruck, in total silence and then I don’t know if I would be able to even think about one specific question...

I would love to meet him in America, in New York, at the Guggenheim, on a day when they are setting up a new exhibit, in an empty museum, early afternoon as daylight shines through the windows. I would talk, as I usually do, about links between the past and the present and I would lose myself in the moment, letting the conversation take its course to actually observe how a brilliant mind looks at simple things.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.