Palermo and its Mafia revisited

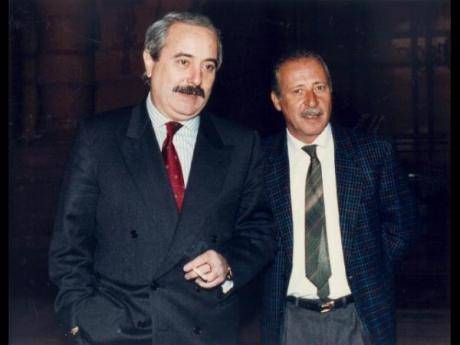

ROME - In February 1986 literally hundreds of reporters converged upon Palermo for the opening of the so-called "Maxi Trial," whose legal framework had been brilliantly crafted by inquiring magistrate Giovanni Falcone together with prosecutor Paolo Borsellino and any number of less famous but equally brave policemen. The most far-reaching prosecution of the Sicilian Mafia in history, the trial would bring 360 convictions of the 475 indicted.

For the occasion, a new cement bunker-like courthouse was built with a tunnel connecting it to the prison. Just before the trial opened, I went into an apartment building overlooking the bunker, to ask Sicilian citizens what they thought of the proceedings. I was taken aback by the answer, which was, "I don't know what goes on in there."

But what I considered the bunker-blind were right, and in fact not alone in not knowing what was going on. Why, for instance, by 1992, after barely six years, would only 60 of those convicted remain in prison? How was it that no less than 300 had made successful appeals that brought their release? Most grievously, to this day the full story of the murders of Falcone and Borsellino twenty years ago, while clearly a direct result of their anti-Mafia prosecutions, remains an enigma shrouded in mystery.

And yet a revival of debate over the events of two decades ago began three years with a formal inquiry into whether or not a secret deal had been struck in 1992 between state authorities and Mafia bosses. As a result of the new investigation, headed by magistrate Antonio Ingroia, the events of two decades past remain today's daily fare, marked by bitter exchanges between the press and respectable politicians holding radically opposed points of view.

Sparking this alleged negotiation was violence. In 1992 the Mafia not in prison went on a killing binge in Palermo that reportedly terrified the entire political class, beginning in Sicily but not only in Sicily. Salvo Lima, a powerful politician in Sicily, personal friend and associate of his fellow Christian Democrat in Rome, Giulio Andreotti, was murdered on January 31, 1992. Then Judge Falcone was murdered on May 23 along with his bodyguards. Next victim in this year of horror was prosecutor Borsellino on July 19, 1992. Bombs recognized as planted by the Mafia were placed in an ancient church near tourist destinations in central Rome and near the Uffizi Museum in Florence. The point - again, still hotly debated - was to frighten the politicians into blocking future Mafia prosecutions and to soften the conditions of detention of the Mafia bosses still in prison.

A total of twelve politicians and Mafia bosses now risk being tried for conducting a very illegal negotiation between Mafia and state. The most prominent politician involved is Nicola Mancino, a leading Christian Democrat who took office as Interior Minister on July 1, 1992, five weeks after Falcone was murdered and just 19 days before Borsellino was similarly killed by a bomb. In the new investigation Mancino is formally accused of having given false testimony during the trial of a former senior police officer with the special operations unit (ROS) of the Carabinieri accused of conducting the negotiations together with the late Vito Ciancimino, a former Palermo mayor convicted for Mafia association and for related money laundering.

Mancino denies the charges. The problem is that this summer court-ordered phone taps reveal Mancino repeatedly telephoning the chief legal counsellor at the Quirinal Palace, Loris D'Ambrosio, 65, and asking for a helping hand. Whether to brush off the appeals or whether actual help from the Quirinal was possible, D'Ambrosio seemed to acquiesce.

On July 26, shortly after the phone taps were legally published (the indictment is in the public domain), D'Ambrosio suffered a heart attack and died.

Current headlines and photographs show President Giorgio Napolitano touchingly placing his hand upon the coffin of his friend and trusted legal counsellor.

In an interview published July 29 in La Repubblica, Ingroia was asked about claims from some quarters that the negotiations between state and Mafia never took place. Untrue, he said: "Sentences [from previous trials] already definitively establish that they did, and we began from those. Today the country has a unique opportunity - I would not like for it to be lost."

And if there was a raison d'etat behind the secret negotiations? If so, he replied, the magistrates of Palermo "could only take a step backward."

At this point, inquiring magistrate Ingroia, braving harsh criticism following the death of D'Ambrosio, and even more, the continuing serious risk to his life from the Mafia, has just accepted a transfer to Guatemala. But even as he takes a step elsewhere, the enigma surrounding the murders of Falcone and Borsellino, of their bodyguards, of Salvo Lima, and of the illicit negotiations they spawned, remains.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.