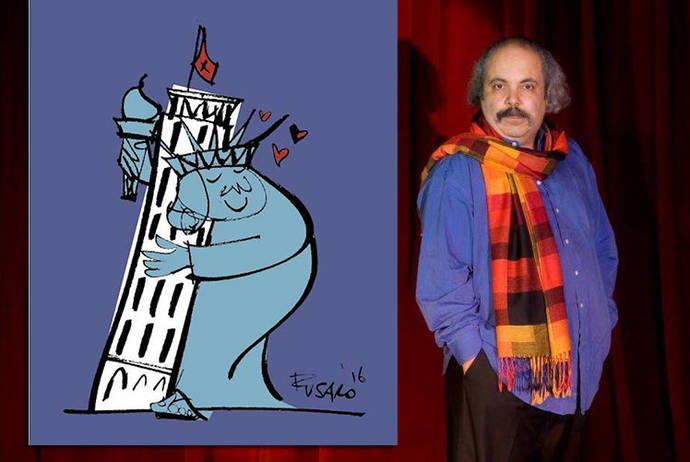

Andrea Purgatori (February 1,1953-July 19, 2023).

Members of the talented, ambitious and idiosyncratic class of 1980 of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University are mourning the death—after a short fight with cancer—of our beloved friend and colleague.

Andrea and I met on the first day of school. I had just returned to my native New York after years of living in Italy and, frankly, my language skills in Italian were better than my English. I missed Italy and he was glad to know someone who spoke his language and knew his country. Andrea was handsome, naturally charming but also baffled and ill-at-ease in this new environment and the high-powered Ivy League graduate school full of people wanting to be the next Woodward and Bernstein.

Our first event as a class was a sailing around Manhattan island on the Circle Line. In three hours, and with no effort, Andrea acquired a pocket full of paper with addresses and phone numbers from women in the class. He then asked if I could accompany him to a store where he could buy a bed, chairs, a table, kitchen equipment, sheets and towels. He took home the sheets and a chair and placed a rush order on the delivery of the bed. The man who would become one of Italy’s greatest journalists apparently had not documented his new address. Instead, one of our female classmates got a surprise. She called me the next morning and asked, “Fred, you know Italy. Is it customary, when a man likes a woman, that he sends her a bed?”

I contacted Andrea and the store and put things right. He was simultaneously mortified and laughing hysterically at these events. From that point forward, when he told me about meeting a special woman, he would say “I might have to send her a bed.”

Don’t get the wrong idea: there was very little of La Dolce Vita journalism in Andrea. He became one of the most courageous and passionate reporters of our time, and not just in Italy. He did decades of investigative reporting, whether the target was the Vatican, the Mafia, NATO, the Italian government or the US government. Though we always kept in touch, I knew that Andrea would sometimes vanish. For example, he went to Libya to secretly meet with Col. Gheddafi when few journalists were granted access.

His most famous story was his years of tireless investigation into the mysterious downing on June 27, 1980 of a passenger flight from Bologna to Sicily in the Mediterranean near Ustica. 81 people died. This became a book and then a film called “Il Muro di gomma“ (the Rubber Wall”). This implied the bounce back and impenetrability he faced in seeking the ugly truth about what really happened. His screenplay won awards and he characteristically vanished for a while—in part for safety and in part to pursue the next story.

In the way that certain Italian media figures do, Andrea was a print journalist and later editor for Corriere della Sera but also an author, broadcaster, screenwriter, actor and activist. He came to environmentalism before most Italians and was, for a time, the president of Greenpeace Italia. In recent years he hosted Atlantide (Atlantis) on the Italian TV channel 7 in which he educated and advocated on crucial issues of survival of the planet.

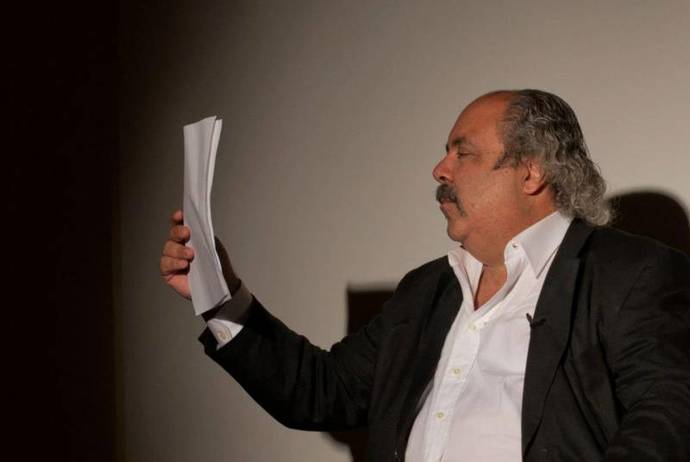

His years and experiences put deep rings under his eyes but I reminded him that his fellow Roman Anna Magnani wore her dark rings like a badge of honor.

Andrea had a rich baritone speaking voice that imbued his broadcasts with authority. Whenever I saw him he would stare at me with those eyes and then, without greeting me or saying my name, ask and answer his own question: “Novità? Niente.” “Any news? Nothing.” This was the central metaphor of his professional life and his restless, passionate never-ending search for truth and justice made him a man who really made a difference.

Fred Plotkin - Author, journalist, public speaker, broadcaster, opera expert as well as an expert on everything Italian