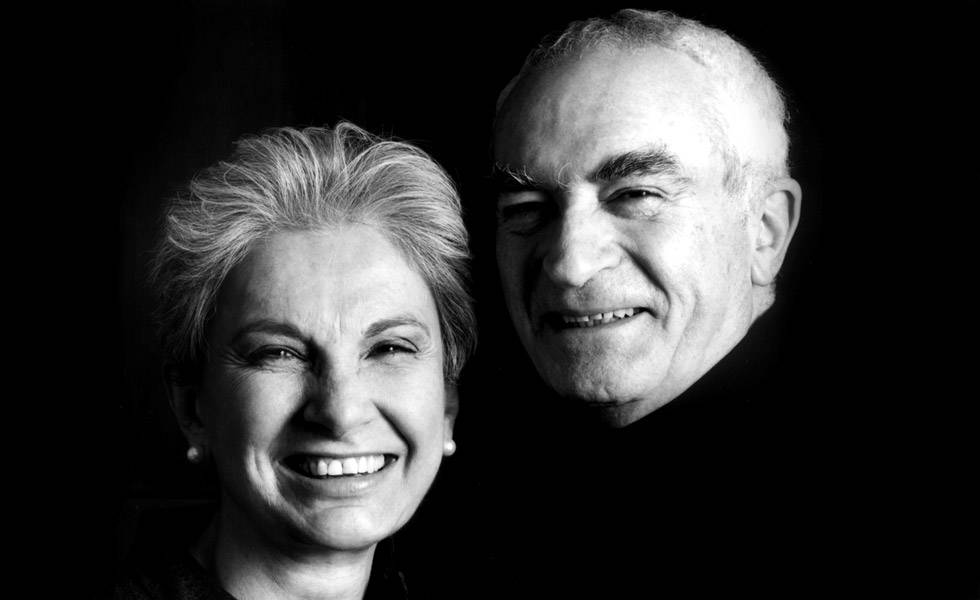

With Massimo Vignelli. Good Design is Responsible Design

“Good design is responsible design. It expresses intellectual elegance rather than its contrary, vulgarity,” says Vignelli, without a trace of aloofness or snobbery.

Those who have been following our conversations will have been gradually taken by surprise by

Vignelli. He’s punctilious, yes, but not boring. He “believes” in discipline but not dogma; he is disciplined and dynamic, flexible and coherent, even if he speaks his own language.

Last time, we spoke about a change he made to his own house. There had been books covering his living room table. A lot of books. We were stunned to discover that Vignelli had figured out how to restore rigor to that space “with a beautiful hidden bookcase. I saw one in Ikea.

The books will be here but you won’t see them and everything will be in order.” So, no top-of-the-line designers? Just a piece of furniture from Ikea that everyone can afford? “Yes, you can find excellent design pieces there! Good, clean designs made with a minimum amount of labor and great modularity.That’s how you do design.”

So here we are, standing beside his hidden bookcases in a space where every contour has been thought out, including the profile of its owner/architect. “Beautiful, right?” says Massimo.

“They’re beautiful because they’re out of sight.” He smiles and continues talking about design in his accessible, pared-down way. “Yes, my style is minimalist. Every language has its rules, everyone has his own style and rules, and that’s why every house is different. My style is more minimalist. You need to take away, take away until there is something left.” The bookcases from Ikea are a case in point.

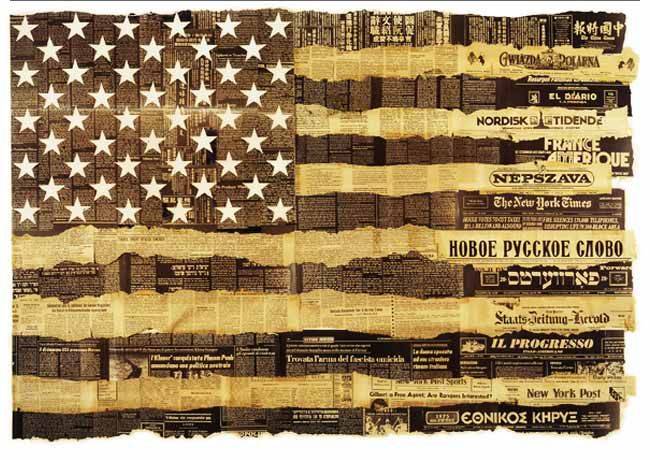

Once again, everything about the house of Massimo and Lella Vignelli suggests a life devoted to design, an intellectual journey culminating in that famous slogan: “Design is one.” What does that mean in laymen’s terms? “‘Design Is One’ was the title of my lecture. The idea goes back to the Viennese [Adolf] Loos, who believed that an architect must know how to do everything, from a spoon to a city. Loos was against specialization because specialization led to entropy and entropy led to the end of creativity.Indee you must be able to design everything—furniture, graphics, packaging, agendas, books, even the clothes I’m wearing. And Lella has designed amazing jewelry. We designed what I’m wearing. I designed the watch too. In our house, everything is designed by us—the chairs and the tables; I designed the books I often read. I live in a space almost completely designed by me. With few exceptions.”

“I love my work because ‘design is one.’ It’s one profession, one attitude. As Italians, we have a long history of codifying design in this way. It has existed for centuries. It was the same for Leonardo da Vinci. In Italy, after the war, we had to do everything ... architects like myself did everything ... The discipline was thesame. The way of thinking, coming up with solutions, was always the same. The mental process was the same and the mental process was discipline. This didn’t exist in American culture. American culture is the culture of specialization. Ours, on the other hand, is the culture of the generalist. Specialists didn’t arrive in Europe till later. So in America in 1977, architecture was facing a crisis. In Italy we thought, ‘But in Europe architects do everything! Not just houses but furniture, and so on!’ That’s how I got my start in America doing the same thing being practiced in Europe.”

And that gave rise to the concept of the coordinated image on which you based your relationship with clients? “Yes, the total coordination of an image is essential. One image for everything, from the logo of a museum to its catalogues to the exhibitions. Or for a company, you begin with the logo to get to the product, the letterhead, the packaging, the store, the displays.” In Vignelli’s opinion, a system of visual identity allows an entity to differentiate itself and become unmistakably recognizable.

Speaking of clients, may we ask what’s the difference between an artist and a designer? “Design is always bound by its relationship with others. Self-expression is the jobofartists. They’retheopposite ofdesigners. Theartistanswers tonoone. Thedesigneralways answers to someone. If you want to make a fork, you have to make a fork someone can eat with, not one that makes it impossible to eat.You can’t make a knife that’s just a blade or just a handle, because striking the right balance of blade and handle is essential tousingit. Thefirstpartinvolves the object itself, the next involves whoismakingtheobject. That doesn’t mean that there’s no room for invention, but there are restrictions.”

And what about the difference between designers and stylists? “Everything depends upon methodology. For example, when a fashion designer creates a style he doesn’t follow a designer’s method. He follows a stylist’s. Styling is futile, disposable. Design is in crisis, not design itself but the mechanism behind it... A lot of younger people think they’re doing design when they’re really stylists.They don’t understand the mental process of design. They think the answer to a situation is to restyle it.”

This is our last “philosophical” conversation with Massimo Vignelli. Next time, having absorbed a few concepts, we’ll get down to details.Together we’ll look at a few design objects by him as well as objects by others that have made their way into his life—and ours.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.