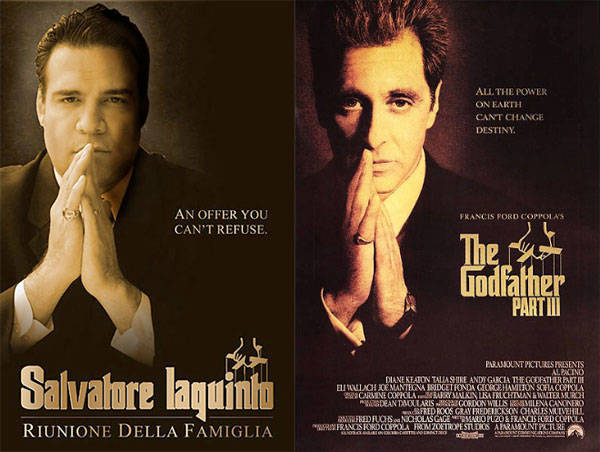

An Offer We Can Refuse

Virginia Beach, Virginia elected official Salvatore Iaquinto is very much off the mark with his original “Godfather” ad and his follow-up commentary. Now, I would preface my comments here by stating that such films (e.g., The Godfather, Means Streets) are significant cultural markers both for the so-called “elite” intellectual arena (some professors use these and other films in undergraduate and graduate courses) and the community at large. We do indeed need to investigate the hows and whys, consider the pros and cons of such cultural products, and, in the end, see where it all leads us by asking what some may consider those impertinent questions. The issue of Italian Americans adopting imagery et alia that have its origins in organized crime (specifically, “mafia” and “cosa nostra”) is complex, to be sure, not at all a black & white issue; and it remains, still, something the Italian/American community at large needs to explore in a most profound and investigative manner. A first step, I would suggest, is to consult some preliminary reading such as Frederic D. Homer, Guns and Garlic: Myths and Realities of Organized Crime (Purdue, 1974). This is a starting point, I would submit, for all those interested in a disinterested, analysis of the phenomenon of “organized crime,” Italian American and not Italian American. Most recently, while different in scope, two keen reflections are available in George De Stefano’s An Offer We Can’t Refuse (Faber & Faber, 2006) and Fred Gardaphè’s From Wiseguys to Wise Men (Routledge, 2006).

The issue of Italian Americans adopting imagery et alia that have its origins in organized crime (specifically, “mafia” and “cosa nostra”) is complex, to be sure, not at all a black & white issue; and it remains, still, something the Italian/American community at large needs to explore in a most profound and investigative manner. A first step, I would suggest, is to consult some preliminary reading such as Frederic D. Homer, Guns and Garlic: Myths and Realities of Organized Crime (Purdue, 1974). This is a starting point, I would submit, for all those interested in a disinterested, analysis of the phenomenon of “organized crime,” Italian American and not Italian American. Most recently, while different in scope, two keen reflections are available in George De Stefano’s An Offer We Can’t Refuse (Faber & Faber, 2006) and Fred Gardaphè’s From Wiseguys to Wise Men (Routledge, 2006).

De Stefano and Gardaphe provide the springboard from which to build a more evolved discussion and/or analysis of the evolution and implications of representations of the Italian/American “gangster” figure. They offer a one-two punch invitation to a re-examination and a new discussion of this contested figure, one that does not fall back on steadfast determinism (read, outright condemnation of those artists who adopt such imagery) but that allows for a more constructive conversation that could lead to a greater—read, more interpretively flexible—understanding of this truly complex phenomenon that so engulfs Italian Americana.

It remains unquestionable, I would contend, that US dominant culture thinking still believes it is acceptable to deride or, for that matter, make erroneous assumptions about certain ethnic groups, Italian Americans being one of them. This is evidenced by how media use such cultural references as catch phrases in headlines and subtitles, as the San Jose Mercury Sun did with reference to the irresponsible musings of Belmar, New Jersey’s mayor Ken Pringle and his comments on “guidos.” This is also evidenced by how journalist Jeff Pearlman catalogued Irish and Italian ethnics a year or so ago in a blog entitled, “Turning a critical eye to the ol’ alma mater”. In that piece, he included the following paragraph:

But I also saw the darker side of my hometown — a gritty, blue-collar Manhattan suburb with a predominantly Irish-American and Italian-American makeup. I still remember the kids who threw pennies at my brother and I because we were Jews; still remember the two crosses that were set aflame in my African-American friend's yard; still remember my eighth-grade teacher instructing us on how “blacks can't ski — they just can’t.” Mostly, I remember the n-word being dropped left and right without punishment. “I love Whitney Houston,” my across-the-way neighbor once told me, “but I hate the color of her skin.”

This surely makes one wonder why Pearlman, an American of Jewish descent writing in 2007 (which suggests, to some extent, that he would be sensitive to ethnic stereotypes as things now presently stand), would engage in such seemingly pre-conceived generalizations about the two “white,” United States Catholic groups par excellence. To impugn anti-Semitism, racism, and violence tout court is, simply stated, a gross misjudgment in human characterization and surely beneath someone engaged in a public discourse that is journalism and popular book-writing, two discursive activities in which Pearlman seems professionally engaged.

The irony in all of this is that Pearlman is ostracizing what he considers the continued, “offensive” practice of knick names for sports teams that refer to Native Americans. To decry bigotry aimed at one group by willy-nilly impugning bigotry to others seems, simply stated, offensive, wrongheaded, and embarrassing to all who are engaged in the enterprise of eliminating such prejudice.

Now, in returning back to Iaquinto, one might indeed argue that, after all, he is Italian American, and as such belongs to the in-crowd with all the so-called rights and privileges of an insider. Well, perhaps! But such a privileged status nevertheless still comes with responsibility. In so stating, I would contend that the notion of responsibility or lack thereof is dependent on one’s position in society. Namely, whether we want to accept it or not, the “public” official—elected and/or appointed—is simply held to a different standard, one that does not necessarily allow for the flippant remark, the off-color joke, or, in this instance, the self-referential ethnic joke that is also the hallmark of one’s public persona, as is the case with all elected officials, appointed administrators, and others in roles of—and I underscore—“public” responsibility.

Such practice by our co-ethnics only gives rise, I would contend, to a sense of entitlement for the likes of those non-Italian/American individuals and entities such as those cited above. After all, they would surely rebut: If the Italian American publicly identifies—albeit jokingly—with the imagery of organized crime (And let us not forget the antics of New York’s most recent Italian/American mayor, in this regard!), what then is wrong with others doing so? Not an entirely illogical question, we need to admit.

It simply does not pass muster that, according to Iaquinto the flier was an attempt at humor and indicative of his desire to distinguish his event from the so-called rubber-chicken event. That said, then, let’s pull out nonna’s sauce recepe if we want to rebuff rubber-chicken dinner! If he were truly not trying to celebrate the culture of organized crime, then why also does he list donor levels such as “Godfather,” “Don,” “Consiglieri” [sic]? If he wanted to celebrate an Italian/American movie, there are numerous other films he could have chosen.

Mr. Iaquinto has succeeded in winning office to an elected position. That said, I suspect he is most familiar with nuance. His statement that “[t]his isn’t a Mafia thing”[; i]t’s a movie thing” is not acceptable; it is not simply an either/or situation. More complexing, dare we say impertinent, is his logic that even though he threw a fundraiser inspired by the movie Pirates of the Caribbean, which included pirate actors, to boot, despite his use of The Godfather this year or Pirates of the Caribbean last year, “[He] by no means condone[s] the activity of organized crime, and [he does not] condone the activities of pirates.” This is then followed by what we suspect is an apology for those who might desire one: “I do apologize if I’ve offended anyone, but that was not the intention.”

Intentionality, unfortunately, is not always a way out of jail card. Sometimes our actions have certain results; and when those results are offensive to the many, a flat-lined apology is in line, not one that is conditionally based. In spite of the enormous successes of many of our sisters and brothers within Italian America, we the community still have much work to do in this regard. We need to investigate such issues further; we need to have those unpopular and uneasy discussions about the above-mentioned issues and other uncomfortable topics amongst ourselves; we need to educate those who need to be educated, even if we come off as seeming thin-skinned. We can partly succeed in these things by, first and foremost, guaranteeing that our culture is represented within the educational system, both correctly and respectfully. We simply cannot tolerate otherwise.

Yet, we should not simply complain and write letters in so doing. In stating as much, allow me to close by underscoring that much of the responsibility lies with those of us within the Italian/American community. Until we step up—and I underscore also as a group voice—and respond, not merely react, in a proactive manner, we will continue to be mocked, ridiculed, and, metaphorically and literally, held hostage to dominant-culture public opinion.

I would, in closing, remind Mr. Iaquinto and others that Renaissance Italy engaged in, as they articulated in Latin, vita contemplativa—what we might call today intellectual meditation on the issues at hand—and vita activa—what we might consider today a vivere civile, a manner of us realizing our worth in active Italian/American citizenship. Such activity involves thinking through issues (popular or not within our community), which is then combined with a philanthropy that is both behavioral (giving of our time and energies) and financial (giving of what we can afford of our means; namely: that patronage in which the Medicis engaged so successfully and thus brought the Renaissance to its celebrated heights). Sitting back and lamenting only is, to be sure, worse than the objectionable actions we abhor.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.