Viva la libertà

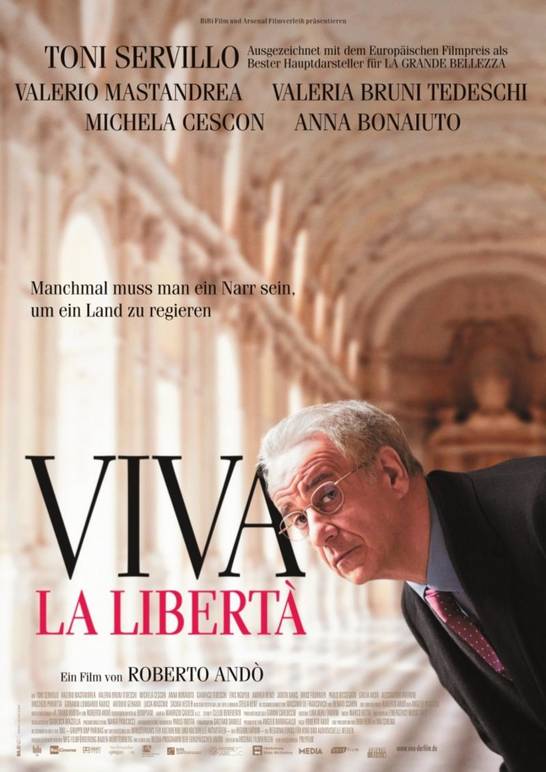

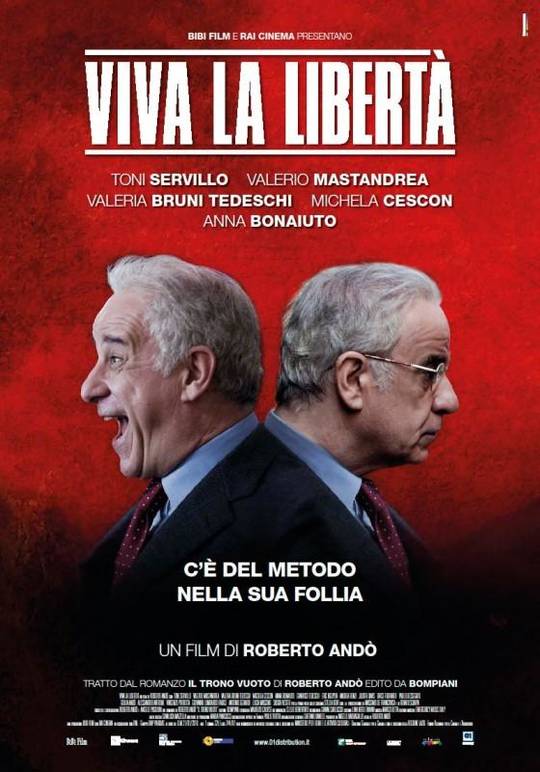

Viva la libertà—which won both the David di Donatello and the Nastro d’Argento— begins with a press conference held by Enrico Oliveri, leader of the left-wing opposition in contemporary Italy. (American viewers will recognize Oliveri as played by the great Neapolitan actor Toni Servillo, best known from Paolo Sorrentino’s Il Divo where he was the late Italian prime minister and powerbroker Giulio Andreotti and Academy-Award winner La grande bellezza where he played the tormented failed journalist Jep Gambardella).

Oliveri, his handlers, and his constituents, all realize the party is trailing badly in the polls as national elections loom. Oliveri is the first to acknowledge that he is the outward manifestation of a more deep-rooted malaise in the party; one that he cannot address. His press conference is interrupted by an outburst from a member of the audience who rises to denounce his failed leadership that will drag the party into a devastating loss in the election.

Curiously, as she is being led away, the protester cries out in Latin “in obscura nocte sidera micant” Which, as any classicist will tell you, is carved into the door jamb of the Benedictine monastery of Subiaco outside Rome: “the darker the night, the more brilliant shine the stars.” While Oliveri’s trusted right-hand man, Andrea Bottini (Valerio Mastandrea) insists she was sent by the opposition to foment a revolt in the party, the phrase is ambiguous in this context. Is it a warning or a prophecy?

Oliveri, overwhelmed and teetering on the bring of a nervous breakdown, decides to leave Italy for a few days, seeking solace and comfort in the company of a former love, Danielle (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi) now living with her film director husband and young daughter in Paris. His sudden and unannounced disappearance throws the party and its functionaries into further crisis.

In desperation, Andrea seizes upon the suggestion of Oliveri’s wife Anna (Michela Cescon) that they press his twin brother, recently-released from an insane asylum, and known by his pseudonym Giovanni Ernani as a philosopher, into Oliveri’s role as party leader. (Ernani is the author of the treatise tellingly titled The Illusion of Living). Since childhood, Ernani had the ability to uncannily mimic his brother; a skill his brother could not reciprocate. He faults his politician brother as one who has “never been able to be himself.” So begins a contemporary fable, a political farce, a Pirandellian play on identity, and a philosophical and ontological puzzle.

While Andrea had thought of Ernani as merely a stop-gap measure, at most for a few days, events escape his well-laid plans. Ernani is (mis)recognized as Oliveri at a restaurant and an intrepid journalist from the Corriere della Sera manages to sneak a brief interview while Andrea is away from the table. Ernani/Oliveri speaks truthfully and bluntly: “If the electorate is disappointed in the poor quality of the politicians, they are to blame.” And Zen-like koans: “Fear is the music of democracy.” Ernani’s words are headline news the next day (“Mai parole piú chiare”) and shock the country. He continues to unabashedly “speak truth to power.” In the process, he rejuvenates and electrifies the party faithful. At a mass rally just before the election, he improvises a stirring speech on “passion” and a polling/electoral earthquake is underway.

Meanwhile in Paris, Oliveri rekindles romance with Daniella, whose husband, Mung, is an internationally known film director. He confides to Oliveri that cinema and politics have a lot in common in that both harbor geniuses and charlatans. Not said, but understood between the film director and the politician is the idea that both mestieri depend on illusion to move their respective audiences. Oliveri also develops a tender relationship with Daniella’s young daughter who serves to ground the weary politician to quotidian pleasures.

Ernani the madman—saner than everyone else around him—revels in life. He returns to his asylum to dance with friends; he seduces the German Chancellor (Merkel) into a bare-footed tango; he is the shot of adrenaline into the weary corpse of the political party. His impassioned speech to the party faithful on the eve of the election reminds audience of the importance of rhetoric—understood in the classical sense—in moving men and women for the public good.

Which raises a few questions: who, in the film, is the real madman? Who determines the boundaries between illness and mental health? Ernani is the court fool who speaks truth to power, but does this mean that Italian politics needs a madman to emerge from its current crisis? Or that only a fool would consider trying to solve Italy’s myriad political problems? As Andrea dryly remarks to Anna: “There a method to his madness. And he’s funny too.”

In the wake of the electoral debacle suffered by American Democrats in the recent elections, is there a message here for Obama? Be fearless, don’t be afraid to win (as Ernani chastises Andrea), free yourself from the constraints of “normal” politics, shed your shoes and your inhibitions and govern in bare feet.

After a few idyllic days, Oliveri returns to Rome from Paris. As he is driven through the Eternal City at night, images of past political glory lay in ruins. He does not seem renewed and willing to take up the reigns of power and responsibility. When Andrea visits the leader’s office early the next morning, he can’t tell if it’s Oliveri or Ernani sitting on the “throne.” Andrea casts an apprehensive peek at the shoes, half expecting the person sitting there to be barefoot (and therefore Ernani). But the politician, whoever he might be, is wearing his expensive loafers. And in a stunning final shot, as the camera closes in on Servillo’s extraordinarily expressive face, the character changes before our eyes from Oliveri to Ernani’s warm and exuberant smile. Hope? Illusion? Pathos? Or inescapable tragedy?

Viva la libertà, directed by Roberto Andó; story and screenplay by Roberto Andó and Angelo Pasquini; produced by Angelo Barbagallo. Director of photography Maurizio Calvesi; edited by Clelio Benevento; music by Marco Betta, costumes by Lina Nerli Taviani. A Bibi Film production with RAI Cinema. Opens in New York on November 7 at Lincoln Plaza and the Quad Cinema and November 28 in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal, followed by national release to select cities.

More info: www.distribfilmsus.com

Stanislao Pugliese, Professor of History and Queensboro Unico Distinguished Professor of Italian Studies

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.