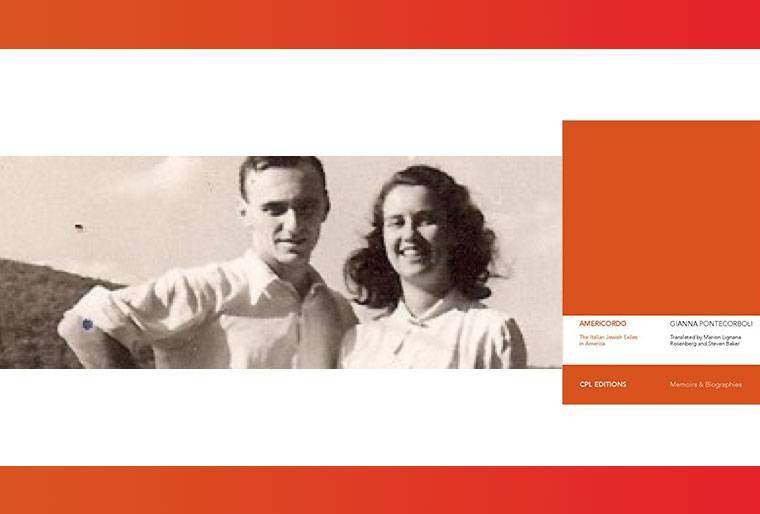

"Americordo": The Italian Jewish Exiles in America

A lesser-known aspect of the history of fascism in Italy and the larger tragedy of the Shoah is the exile of Italian Jews to America. Yes, some Americans of a certain age are enamored of Vittorio De Sica’s 1971 Academy-Award-winning film “The Garden of the Finzi-Contini” (often not aware that it is based on a 1962 novel of the same name by Giorgio Bassani.)

Some Americans are readers of Primo Levi, especially after his extraordinary Periodic Table wastranslated into English and praised by such writers as Susan Sontag, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. And some Americans are conscious of the long-running debate on the role of the Vatican and Pius XII during the Nazi occupation of Italy. But few Americans—or Italian-Americans for that matter—are familiar with the plight and influence of 2,000 Italian Jews who fled fascist Italy under the most difficult circumstances after the appearance of the “Manifesto of the Racial Scientists” in the summer of 1938 and the subsequent promulgation of anti-Semitic legislation—based on the notorious Nuremberg Laws of Nazi Germany—several months later.

Now, Centro Primo Levi Editions has published an English translation of Gianna Pontecorboli’s Americordo, and the story should be better known.

When asked to explain the generis and project of CPL Editions, Alessandro Cassin, Director of Publishing for Primo Levi Editions, recalled “For about 10 years, the activities of Primo Levi Center, were tied to our public programing, to our online activities, and to the synergies between the two. As our web presence grew through the online monthly Printed Matter, we realized that the more content we provided the more interest we stimulated. In other words, publishing books is a natural extension of our website.”

(The Centro Primo Levi is on West 16th Street while CPL Editions last year renovated the old S. F. Vanni Bookstore on West 12th Street, steps from the Casa Italiana of NYU.) “One of our objectives,” Cassin continued, “is to present the history, culture and traditions of the Jews of Italy, as to stimulate further study in this field. One of the main problems is that few of the texts —both classics and new— are available in English, so we began translating a selection of books we believe are important.”

Pontecorboli’s writing—admirably translated by Marion Lignana Rosenberg (who died tragically during the project) and Steve Baker of Columbia University—is clear and direct, thankfully fee of the rhetorical excess that sometimes accompanies the subject.

This book is a humble homage to the history of some 2,000 Italian Jews who crossed the ocean to flee the Fascist regime’s unjust racial laws, having understood early on the tragedy in which those laws would culminate only a few years later. This story has never been told in its entirety, though many of the exiles have written books and personal memoirs.

When fascism came to power in 1922, some Italian Jewish families welcomed the new regime, an indication of how assimilated into the communities had become. With no anti-Semitic platform to speak of (but numerous anti-Semites in their ranks), the fascists didn’t appear at first to be as dangerous as their German counterparts. Italy had Jewish prime ministers and Rome had a Jewish mayor when France—home of the Enlightenment—was convulsed by the Dreyfuss Affair. Were not the Jews of Rome the “Pope’s Jews”? Had not Mussolini promised to protect Italian Jews since “they had wept at Caesar’s tomb”?

But by the mid-1930s all had changed and the first Italian translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, while little noticed at the time, was an ominous shot across the bow. By the fall of 1938, thousands were faced with a wrenching decision: to stay or go into exile?

It was a disparate group. In addition to architects, musicians, artists, journalists, designers, mathematicians, and no less than three later Nobel Prize winners, there was a seamstress, a door-to-door salesman . . . This is a collective portrait of ordinary and extraordinary people; a polyphonic biography. Appropriately enough, the story begins with Pontecorboli recalling the arrival back in Italy of an aunt and uncle who had fled in 1938.

Giuseppe Prezzolini, one of the prominenti in his role as Director of the Casa Italiana at Columbia University, astutely observed that “These Italian Jews were . . . entirely different. They constituted a special emigration. Once arrived they never set about asking for assistance; instead, they actually gave assistance, each helping the others. They didn’t mingle with New York Jews or even with Italian-Americans. . . As far as Jews were concerned, they were Italians, and Italian-Americans considered them Jews. For Americans they were the subject of wonder and awe.”

Author Gianna Pontecorboli was born in Camogli (Genova), earned a degree in Economics from the University of Genova in 1968 and has had a distinguished career as a journalist in Italy and the United States. She writes often about politics, culture and the economy. Currently, she is the UN and US correspondent for the Swiss newspaper Corriere del Ticino; she is also a writer and founding partner of the online paper Lettera 22.

She kindly and graciously responded to several questions about the book.

Obviously, this is a very personal work. Can you explain how the idea came to you and your own history?

“I think the most interesting thing may be to talk about how this book was born. I’d like to start with a small, personal story. A few years ago we organized a family dinner in Genova. We were five cousins who came from three different families. At a certain point the conversation came around to the “American uncle,” my mother’s brother who had decided to move to the US together with a cousin shortly after the passage of the Racial Laws.

At that moment we realized that all five of us had incredibly vivid memories of when he and his wife visited Italy. We were all children, but none of us forgot the excitement that enlivened the family and especially their fascinating stories. And, at the same time, we remembered the tension we perceived in our parents questions.”

“When I came to NY at the end of the 1970s the environment in which my aunt and uncle had lived was still largely intact and so it was natural that it aroused my curiosity and the emotions of my childhood. I had the opportunity to meet many of the Italian Jews who had arrived after 1938 thanks to my work, and I was fascinated by-the fact that they were perfectly integrated with Americans, Jews, and Italians, while at the same time remaining ‘different.’ And I was impressed by the success that many of them had had, in spite of the difficulties they encountered.”

“I immediately understood that their story deserved to be told. I still remember perfectly visiting one of them in his house in Larchmont, outside of NY. On the way back I told the person who was accompanying me, ‘this story deserves a book. I will have to write it.’However the time was not yet ripe, both because there was not yet the interest there is now in revisiting that period in time and because I realized immediately that the experience and suffering of the past still haunted many of them and it would be difficult to for them to tell an impartial and serene tale.”

Do you discern a difference (ideological, psychological, political, cultural) between those who choose exile and those who remained behind? Was there any antagonism between the two groups?

“The exiles who chose America belonged primarily to the Jewish upper middle class, which had the money and the contact to take a real leap into the darkness. The majority were professionals or intellectuals who had lost their work because of the racial laws. Many--but not all of them--were antifascists. As far as I know, their decision to leave was received with sorrow but also with understanding by those who decided to stay and they were received with open arms when they went back after the war.”

What personal and intellectual qualities did the exiles carry that helped them become successful in America?

“Obviously cultural and intellectual qualities played a major role. One of the factors was the idea that they had lost their support system and they had to prove themselves in the new world. The friendship of the other exiles and the help of different organizations like the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue were crucial to reassure the weakest."

How is this history of Italian Jewish exiles understood today in Italy?

“I had a lot of interest when the book came out in Italy. It is a new story for the larger Italian public.”

Alessandro Cassin promises that “CPL Editions will continue to expand our offering of books that relate to the Jewish presence in Italy, from ancient time to the present, from a variety of points of view.” They have also created a CPL Editions APP—which can be downloaded for free at iTunes or google play—and “allows our readers to be updated on our new books and on read Printed Matter on their phones and electronic devices.”

The nearly four-dozen black and white photographs evoke a world we forget at our peril. From Rome, Milan, Fiume, Venice and dozens of other Italian towns and cities, to New Haven, CT, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Princeton, NJ, it was another chapter in the millennial history of the Diaspora. With a useful bibliography, 80 short biographies and a preface by Furio Colombo, this is a valuable and necessary book that will appeal to both scholars and general readers alike.

Stanislao Pugliese is the Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies at Hofstra University.

--

AMERICORDO: The Italian Jewish Exiles in America, by Gianna Pontecorboli; translated by Marion Lignana Rosenberg and Steven Baker; Centro Primo Levi Editions 2015; 380 pp. paperback, $12.00; available as an ebook; primolevicenter.org.

Reading and Discussion with author and Judge Guido Calabresi, Monday, March 28, Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò NYU, 24 West 12th Street, 6:00 p.m.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.