In 1959 Columbia University Italian Professor Olga Ragusa published “Women Novelists in Postwar Italy” in the journal Books Abroad out of the University of Oklahoma. It was quite likely the first time English-language readers, even just those reading obscure academic journals, would have come across Gianna Manzini’s name. Without social media or even major news organs, like the New York Times, covering her work, transnational academics were Manzini’s best bet in getting her books read outside of Italy.

In her native Italy, however, Manzini (1896-1974) had been publishing her short stories and novels as early as 1924, when she was 28 years old. Her writing first appeared on the cultural pages of newspapers such as Florence’s La Nazione and Milan’s Corriere della Sera, although later she was published by large Italian publishing houses and won the prestigious Viareggio Prize (1956) and the Premio Campiello (1971).

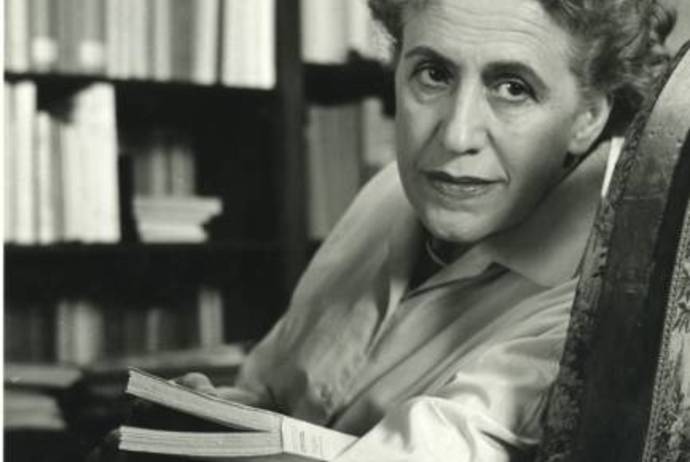

Gianna Manzini with the critic Mario Praz (1946)

On reflection, it’s not surprising that few had heard of Manzini when Ragusa, in 1959, included her in a list of other contemporary Italian women writers who Ragusa noted were part of the “coming of age of the woman writer in Italy.” As Ragusa was clearly aware women writers, and Italian women writers specifically, had long been seen by both critics and the general public as secondary in artistic worth to their male counterparts.

In fact, Manzini, even with her early successes and support by such well-established writers as Eugenio Montale, was not shielded from patriarchy’s blows. Like so many other talented women writers, her oeuvre has been by and large neglected by all but a handful of academics. Thus it is no small gesture that Italica Press takes on the English-language publications of her work today in this and other recent similar publications.

Gianna Manzini's Sulla soglia (1973)

First published in 1973 in an anthology (also titled Sulla soglia), Threshold, the novella Irena Stanic Rasin and I translated and just published, deserves a spot within the tradition of postmodern fiction, with its evocative and slippery use of symbolism, its self-consciously confusing temporality and its unclear relationship between space and perspective. At the same time, it’s imbued with an immediacy of emotion and personal subjectivity unique among postmodern fiction. As such Sulla soglia might rightly be situated within the genre of creative nonfiction or even postmodern memoir. Also significant is how Manzini’s play with language brings into focus inner struggles and emotional expressions specific to women and women’s everyday experiences.

The novella, Sulla soglia, offers an experimental and introspective look at a daughter’s relationship to her mother’s last days. Her writing style and her subject material are raw, unnerving, and fragile. Take these two passages from the new translation—one, an example of her metacritical-esque references to language, the other, a plainly-written description of the pain of living near the edges of death:

Every place has its forbidden language. I was certainly using some inadmissible words — words that break — and their fragments hurt everybody. They would bleed, if they could.

“I remember, Mama, when swallowing became difficult for you. It became

obvious when you had to take your medicine. Oh, as usual, I would believe in it blindly.

‘It doesn’t go down,’ you would say, bewildered. And I, ‘Try, try harder.’ Until you

crushed the capsule against your palate, and then you had to rinse out your mouth.

You were frightened. I can still see your bewildered and astonished eyes and your head,

which, falling back, was sinking into the pillow in such a strange, strange way. Your

small head, almost only hair and eyes, was plunging faster than a stone would. ‘I can’t.

I can’t take it any more. My throat. My throat won’t take it.’”

Manzini’s general anonymity has sometimes been explained by pointing out that her writing is too oblique, her syntax too challenging. Following this logic, translating her work into English would seem to be a senseless act.

But 43 years after the first publication of Sulla soglia, in an era when Elena Ferrante, an unidentified Italian writer has become an international sensation, in great part because of the success of the English-language translations of her remarkably honest and well-crafted novels, let's also return to reading those writers, like Manzini, whose work has remained on a threshold.

____________________________________________________________

Gianna Manzini's Threshold (Italica Press, 2016)

Nota Bene: This blog post is liberally borrowed from my Introduction to the translation, “The Forbidden Language of Little White Boots and Butterflies: An Introduction to Gianna Manzini’s Sulla soglia (Threshold),” (by Laura E. Ruberto), found in Gianna Manzini’s Threshold, Translated by Laura E. Ruberto & Irena Stanic Rasin, Italica Press, 2016.

.jpg)