Introduction

Frank Lentricchia admired Don DeLillo’s rejection of the Italian American home as the source and manifestation of DeLillo's creativity. In his 1991 book Introducing Don DeLillo, Lentricchia wrote:

“…writers like DeLillo [ignore the advice to] write what you know … a snapshot of your neighborhood and your biography…Writers in DeLillo's tradition have too much ambition to stay home … rather writers such as DeLillo: leave their home, region, ethnicity, and the idiom they grew up with behind when they write” (p.67-68 emp.+).

Similarly, Lentricchia, practicing what he preached, did not “stay at home”. That same year 1991, he began writing his first novel The Edge of Night.

James C. Mancuso, in his review of the book writes;

“In Edge of night, which he subtitles A confession, Lentricchia describes the pilgrim's road by which "the favored grandson" of an Italian-American, working class family travels from Utica, New York to a hallowed sanctuary in Durham, North Carolina. He evocatively describes as the dust and heat, as well as the pleasures of the caressing breezes, cool shade, and sustaining food and drink experienced by pilgrims on that road. (Connections to the Great Italy-USA Immigration --- L'Avventura http://www.sersale.org/mancuso/lentrevu.html)

You can take the boy away from Little Italy. But…

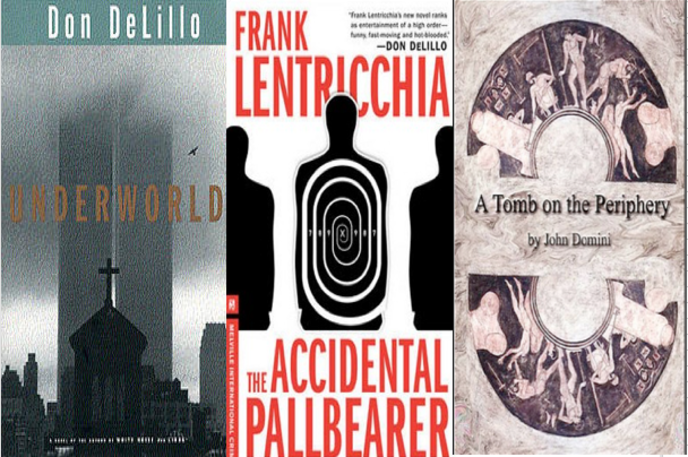

In 1996, five years after Lentricchia celebrated DeLillo’s rejection of his Italian American home, DeLillo negated the celebration “in spades”; writing what is arguably the most brilliant, literary or social scientific rendition of Little Italy in print – Underworld. In that same year, Lentricchia followed suit with Johnny Critelli, and The Knifemen, novellas set in his Little Italy hometown Utica, New York. And again, in 1999 with Music of the Inferno part of the SUNY Series on Italian American Culture, which garnered a positive comment from Don DeLillo – no less.

Almost twenty years after DeLillo went back to Bronx Little Italy in Underworld; with the publication of The Accidental Pallbearer, Lentricchia again went home to Little Italy Utica, New York. For someone who in 1991 consider it a virtue for a writer to “leave their home, region, ethnicity, and the idiom they grew up with behind when they write”; Lentricchia spills a lot of ink on Utica. And, again DeLillo raved about the book.

(Note, an interesting aside: early prints of “Pallbearer” had DeLillo’s praise on the front cover. In current prints, DeLillo is replaced with a superlative from prolific pop crime novelist Lisa Scottoline. I’d guess the publisher realized that low-brow crime buffs would largely not be familiar with or impressed by a high-brow postmodern writer like DeLillo. Worst, a recommendation from DeLillo may mislead crime readers into think Lentricchia wrote the same kind of postmodern ‘stuff’ as DeLillo and thus ignore the book. A recommendation, on the other hand, from Scottoline, who writes volumes about her south Philly Italian American neighborhood, communicates to the reader that Lentricchia is a straight up gumshoe story teller like her. Also, it is interesting that the publisher substituted one Italian name author (DeLillo) for another (Scottoline)…But I digress)

Both DiLillo and Lentricchia with their respective novels demonstrate the tenaciousness of southern-Italian American culture. Both consciously and willfully left Little Italy behind physically and intellectually. However, both found that physical and intellectual distance does not equate to cultural distance.

You can take the boy away from Little Italy.

But you can’t take Little Italy away from the boy.

And the boy is always in the man.

Similarly, southern-Italian Americans in mass left homogeneous Little Italy behind beginning in the 1950s; moving to the heterogeneous suburbs. Nevertheless, three generations later, southern-Italian American culture is still vibrant and a very distinct subset of the totality of Cultural America.

The Accidental Pallbearer – “…a snapshot of your neighborhood”

With Accidental Pallbearer Lentricchia twice reversed himself. First, he profoundly changed aesthetic genre. Whereas The Edge of Night is a highbrow literary undertaking that James Mancuso calls post-modern (whatever that means other than incomprehensible to ‘folks’), The Accidental Pallbearer on the other hand is classic gumshoe ‘who done it’ private eye crime story. Indeed, it’s billed as the first of what will become an “Eliot Conte Series” – kind of like Patricia Cornwell’s Scarpetta series of crime novels.

Secondly, having jettisoned any pretentions of writing literature (in the academic honorific sense of the word), he came home, as it were, and wrote the very “snapshot of neighborhood, ethnicity and idiom” that in 1991 he praised DeLillo for “leaving behind”.

As a crime novel it is quite good. Not the greatness of Cornwell’s early Scapetta novels but much better than her more recent contrived works. The plot of Accidental Pallbearer is a tad too complex to fully develop in 208 pages. By current publishing standards, the typical crime novel is about 300 pages long. He could have easily used another 100 or so pages to fully develop all the intricacies of the plot. Nevertheless, it is a good read that crime buffs would enjoy and appreciate.

More to the point of the present discussion, the protagonist Eliot Conte is the grandchild of southern Italian immigrants. He loves to cook and eat Italian food, his idiom is laced with Italian words and expression, etc. In short, he is imbued with southern Italian culture. However, there is no mention of the southern Italian homeland from which his grandparents emigrated. There is a short anecdote about his grandparents, but they are almost a mystical past and southern Italy is non-existent.

In short, Eliot is the typical southern-Italian American; completely uninformed about the history of his culture and people further back than a generation or two. And, Lentricchia like the vast majority of Italian American literati perpetuates that ignorance of south of Rome cultural roots.

Against this tide of history begins at Ellis Island stands John Domini’s “A Tomb on the Periphery”. Also a crime novel; set in Naples. But, not a pop culture gumshoe private eye melodrama. Rather, Domini achieves literary quality without literati esotericism a la postmodern machinations. More importantly, from the point of view of this piece, it melds contemporary Neapolitan culture with its ancient past, demonstrating that southern Italian culture, unlike Athena, did not “leap from the Head of Zeus a complete form”; rather, it evolved over millennia.

The masses of southern-Italian Americans are ignorant of their millennial history and they are consciously and systematically kept in a state of ignorance by the Italian American literati who either are in love with northern Italian Renaissance culture and its contemporary progeny or are nostalgic for Little Italy and can’t see the history before it.

Writers and professors like DeLillo and Lentricchia are both the product and perpetuators of this southern-Italian American cultural and historical myopia.

In sum:

If there is no history, then there is no culture; if little history, then little culture – hence, Italian American preoccupation with FOOD. That’s the little cultural thread we fanatically hand on. Factor food out of the discussion of Italian American culture, and what’s to talk about? Nostalgic sentiments?

Whereas Domini writes a crime story that beckons southern-Italian American’s to their long mighty history and culture, urging us to get beyond the sausage at San Gennaro, The Accidental Pallbearer, consistent with the milieu of the Italian American literati, is a work of nostalgic sentiment (the old neighborhood, food, idiom) wrapped in a crime story.